I. Compline in the Dominican Rite

Those who would like to see the music that I will describe in this post may do so on the sidebar link to "Antiphonarium S.O.P. (Gillet 1933)," consulting pp. 83-135.

Perhaps the most famous liturgy of the Dominican Office is that of

Compline, and its format shows that the Dominican Office is in origin that of canons, not monks. This is indicated by the presence of the canticle of Simeon, the

Nunc Dimittis (Lk 2: 29-32), at the end before the Collect, an element missing from the Benedictine Office, but found in the Roman. Compline, and especially the Procession that followed it, is the subject of so many stories of visions and miracles in Dominican lore that it was the one element of the choir Office not dispensed by the so-called lector's privilege.

That privilege, which dates back to the days of St. Dominic himself, exempted friars holding the "lectorate in sacred theology" and involved in full-time writing and teaching, as well as those appointed "preachers provincial" or "preachers general," and involved in full-time preaching, from attendance at the daily choral Office and sung conventual Mass. They where permitted to recite the Office privately, along with saying their private masses. Lectors and preachers did, however, have to attend Compline, so much was it considered part of our spirituality. This privilege was abolished in 1968, during the reforms after Vatican II.

In its basic structure, Dominican Compline remained unchanged from the liturgical reform of Humbert of Romans (1256), until the adoption of the Roman Office in 1969, with the exception of the Psalms. Those who know the older Roman Office will recognize the structure. It began with the examination of conscience: the invocation

Noctem quietam, the chapter

Fratres sobrii, the verse

Adiutorium nostrum, and the

Confiteor in its short Dominican form by the prior and the community. Usually the confession was made standning and bowed profoundly, but during Lent, Ember Days, Vigils and other days of penance, it was done while "prostrate on the forms" as seen in this photo. The

Proprium O.P. of 1982, which provided for Dominian elements to be included in the new Mass and Office allows the retention of this custom (n. 38c).

Then followed the Office itself: the verses

Converte nos and

Deus in adiutorium, the antiphon

Miserere and Psalms 4, 30, 90, and 133; the chapter

Tu in nobis, the short responsory

In manus tuas, the hymn of the season (usually the

Te lucis) with its verse

Custodi; the

Nunc Dimittis with its antiphon

Salva nos; the short

preces (if a feria), the collect

Visita, and the blessing by the prior. I will discuss the

Procession after Compline later. In 1922 we adapted the Psalter reform of Pius X and the traditional Psalms (minus Ps. 30) were relegated to Sunday. The other days of the week had the same cycle of Psalms as the revised Roman Office--with Roman antiphons when no Dominican variant could be found. Otherwise the traditional office remained intact.

In addition, Dominican Compline had rich temporal and sanctoral variations. In common with the Roman, we had a rich variety of melodies for the hymn

Te Lucis, which varied according to the grade of the feast, the time of year, and the particular feast--usually paralleling hymn melodies from the major hours. In addition, this hymn had extra verses and doxologies, especially for Marian feasts, as did the hymn

Christe qui lux (Lent) and

Iesu nostra redemptio (Easter time). We also used the short response

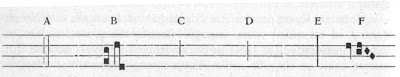

In manus tuas with alleluias on solemnities as well as in Easter time. Here is an example of the Te Lucis for Saturday evening, in my opinion one of the most beautiful of the melodies. It is from the famous fourteenth-century Poissy Antiphonal:

In addition to this, our Office provided a variety of proper and common antiphons. For the Psalms these not only include the triple

Alleluia of Easter time, but also antiphons for Christmas Eve (

Completi), Christmas Day (

Natus est), Epiphany (

Lux de luce), Purification (

Sancta Dei), Annunciation (

Ecce Virgo), and two versions of that for the other Marian feasts (

Virgo Maria). The variety of antiphons for the Canticle of Simeon was even greater: Christmas Eve (

Ecce completi), Purification (

Nunc dimittis), Annunciation (

Ecce ancilla), Lent (

Evigila), Passiontide (

O Rex), and Marian feasts (

Corde et animo and

Sub tuum).

The special

Nunc Dimittis antiphon of Eastertide

Alleluia, resurrexit Dominus, alleluia, sicut dixit vobis, alleluia, alleluia in mode 5 is paralleled in melody and structure by others using a scriptural verse and four alleluias: those of Christmas Day (

Verbum caro factum), Epiphany (

Omnes de Saba), Ascensiontide (

Ascendens Christus), Pentecost (

Spiritus Paraclitus) and Corpus Christi (

Panem quem ego dedero). In 1948, one other antiphon on this model was created:

Haurietis for the feast of the Sacred Heart. Here is example of this famous Alleluia chant, that for Easter, again from the Poissy Antiphonal:

During Lent on Saturdays, Sundays, and major feasts, the short response was replaced by the famous responsory,

In pace. Every friar (yes, every friar) took a turn, in order of religion, singing that chant's verse, as the others sat and mediated (?). The same discipline applied to the responsory,

Media vita, which was used as the "antiphon" for the

Nunc Dimittis during the third and fourth weeks of Lent. This respond contains an interesting Latin version of the

Trisagion. For those of us who are not great singers, its verse was mercifully simple and short. The

In manus tuas of Passiontide, dropped, of course, the

Gloria Patri; and was replaced in the

Triduum by

Christus factus (sung simply to Psalm tone 8b) and by the antiphon

Haec dies on Easter Sunday to Tuesday.

Before you begin to think, how could the Dominicans have abandoned all this? You should know that we have not. According to the

Proprium Officii Ordinis Praedicatorum (1983), which I mentioned earlier, all the chants I have mentioned have been approved for use with the new Liturgy of the Hours. The only major change is that the

Media vita is now restored to its more logical use as a responsory. The proper also approved the use of the Dominican

Confiteor for the examination of conscience. I know that English versions of many of these chants are use in the American Dominican Provinces, along with the original Latin versions. And now:

II. The Processions after Compline Before I describe the ceremonies at the end of Compline in the Dominican Rite and the Liturgy of the Hours according to Dominican use, here is a link to a video of the Salve Procession at San Clemente in Rome, the Irish Dominicans, accompanied, on this occasion, by some visitors who can be recognized as they are not in Dominican habits. You will note how the procession moves from choir to the people's part of the church, has the genuflection at the traditional time, and the sprinkling with Holy Water.

Before I describe the ceremonies at the end of Compline in the Dominican Rite and the Liturgy of the Hours according to Dominican use, here is a link to a video of the Salve Procession at San Clemente in Rome, the Irish Dominicans, accompanied, on this occasion, by some visitors who can be recognized as they are not in Dominican habits. You will note how the procession moves from choir to the people's part of the church, has the genuflection at the traditional time, and the sprinkling with Holy Water.Although

Dominican Compline is musically and liturgically well known, perhaps even more famous is the procession by which it is traditionally followed. The institution of the singing of the

Salve Regina after Compline, according to Bl. Jordan of Saxony, who witnessed the events, occurred in the Dominican priory of Bologna about 1221. A Brother Bernard had been tormented by doubts and temptations. Jordan, then Master of the Order, decided that the community would invoke the help of the Blessed Virgin through a penitential procession while singing the antiphon

Salve Regina after Compline. Bernard was immediately freed of his tribulations and the practice was spontaneously imitated in Lombardy and then throughout the entire Order. The sprinkling of the friars with Holy Water by the prior or hebdomadarian was added at this time or soon after.

The

Salve Regina (see Dominican version to the right), sung after Compline, is not original to the Dominicans. The Dominican melody is part of a family of twelfth-century variants on a more ancient melody, of which the solemn Roman-Benedictine, the Carthusian, and others are also examples. The antiphon itself dates to the late eleventh century and was in common use first among Benedictines and Cistercians. The Cistercians already used it as processional chant, before or after chapter meetings, in the 1210s. But its use for a procession to the people's part of the church is distinctively Dominican. Traditionally, in the Dominican Rite, the antiphon for the Virgin after Compline never varies, but is always the

Salve Regina, but an

alleluia is added to it and ti the verses following it during Easter time.

The ritual of the

Salve Procession is as follows. On every day of the year (except Wednesday, Thursday and Friday of Holy Week) two acolytes, wearing surplices and carrying candlesticks with lighted candles, took up their positions before the altar. For the intoning of the

Salve, the entire community fell to their knees and remained kneeling until the word "Salve" had been finished; then the friars rose and went in procession behind the two acolytes to the outer church of the laity. There the brethren knelt in place facing the altar or shrine and were sprinkled with holy water by the hebdomadarian. By the late middle ages, the custom was introduced of the community also kneeling at the words:

Eia ergo advocata nostra. The antiphon ended, the acolytes sang the versicle:

Dignare me laudare te, Virgo sacrata; to which the community responded:

Da mihi virtutem contra hostes tuos. The final prayer

Concede nos was the sung by the hebdomadarian.

By the fourteenth century, it become a common practice to sing the antiphon

O lumen Ecclesiae, the Magnificat antiphon of the feast of St. Dominic, while returning in procession to the choir. The procession ended with the verses and the collect of St. Dominic. Like the

Salve, this antiphon and its verses had

alleluias in Easter time. But its use was never absolute. Some provinces and houses substituted the antiphon of another saint for the

O Lumen.

Those interested in the way medieval music was put together will find the thirteenth-century antiphon O Lumen to have interesting similarity to another well-known piece of chant:

This kind of borrowing was very common in the middle ages, and in the modern period.

There are two other processions traditionally attached to Compline. The first, and best known, is the interpolation between the

Salve and

O Lumen of a

Procession to the Holy Rosary Altar or shrine, while singing the

Litany of Loreto. This procession is early modern in origin. The Litany concluded with the singing of the prosa

Inviolata and the collect. In Easter time, the

Inviolata was replaced by the

Regina Caeli, sung to a Dominican version of the solemn tone. The other procession was on the first Tuesday of the month and also placed between the

Salve and

O Lumen. This is the

Procession to the Altar of St. Dominic, during the singing of the prolix responsory

O spem miram, which is taken from Matins of the saint. There two are not the only processions that local priories and provinces added to Compline, but they are the ones most commonly performed, even today.

Again, these chants have been preserved for use with the new

Liturgy of the Hours according to the provisions of the

Proprium Ordinis Praedicatorum of 1982. The use of the

Salve throughout the year may be maintained, as well as, if desired, the procession and the verses and collect. In addition, provision is made also for the substitution of the famous antiphon

Sub tuum presidium or, during Easter time, the

Regina Caeli. The Litany on Saturday may also be continued, and an alleluia added to the

Inviolata during Easter time. Finally, the traditional freedom of choice for ways of commemorating St. Dominic is preserved. There is the option of singing the

O spem miram or the

Magne pater, another well-known antiphon from the saint's office, in place of the

O Lumen. I have seen all of these options taken, using the original Latin or English adaptions.

These musical options are included in the new Compline Book available for consultation or download on our sidebar at

Completorii Libellus Novus (2008).

And here is a link to an (admittedly truncated) celebration of the Salve Procession at Blackfriars, Oxford, December, 2007, with thanks to Engish Dominican students.

The practice of Prostratio in Formis ("prostration on the forms"), or simply Prostratio ("prostration"), is probably as old as the Dominican Order and rubrics on it are found in the Ordinary of the Humbert Codex (1256), the codification of the Dominican Rite. The rubrics on this rite were codified in their modern form in the Jandel Caeremoniale of 1869, nn. 781ff., which I will outline. Prostration on the Forms is made by kneeling, with the capuce raised, in the choir stall and bowing over the kneeler of the stall, with the head inclined. You can see this gesture in the image to the right, which shows the practice in a French Dominican house during the 1950s. When there is no "form" or kneeler, the gesture is made by kneeling on the ground and bowing low.

The practice of Prostratio in Formis ("prostration on the forms"), or simply Prostratio ("prostration"), is probably as old as the Dominican Order and rubrics on it are found in the Ordinary of the Humbert Codex (1256), the codification of the Dominican Rite. The rubrics on this rite were codified in their modern form in the Jandel Caeremoniale of 1869, nn. 781ff., which I will outline. Prostration on the Forms is made by kneeling, with the capuce raised, in the choir stall and bowing over the kneeler of the stall, with the head inclined. You can see this gesture in the image to the right, which shows the practice in a French Dominican house during the 1950s. When there is no "form" or kneeler, the gesture is made by kneeling on the ground and bowing low.